During phase transformation or twinning the orientation of a crystal rapidly flips from an initial state oriA into a transformed state oriB. This relationship between the initial and transformed state can be described by an orientation relationship OR. To make the situation more precise, we consider the phase transformation from austenite to ferrite via the Nishiyama Wassermann orientation relationship

% parent and child crystal symmetry

csP = crystalSymmetry('432','mineral','Austenite');

csC = crystalSymmetry('432','mineral','Ferrite');

% the orientation relationship

p2c = orientation.NishiyamaWassermann(csP,csC);Now an arbitrary Austenite orientation

oriA = orientation.rand(csP)oriA = orientation (Austenite → y←↑x)

Bunge Euler angles in degree

phi1 Phi phi2

156.958 161.468 197.878is transformed in one of the following Ferrite orientations

oriB = variants(p2c,oriA)oriB = orientation (Ferrite → y←↑x)

size: 1 x 12

Bunge Euler angles in degree

phi1 Phi phi2

95.6328 91.0043 16.4349

330.335 152.635 96.6679

23.6163 57.205 298.401

311.882 62.194 268.771

186.966 63.9508 170.719

46.1511 49.9141 104.876

183.862 83.1959 351.609

80.4228 132.659 125.129

110.65 31.2299 298.288

54.5999 141.255 286.055

333.585 64.3114 78.9078

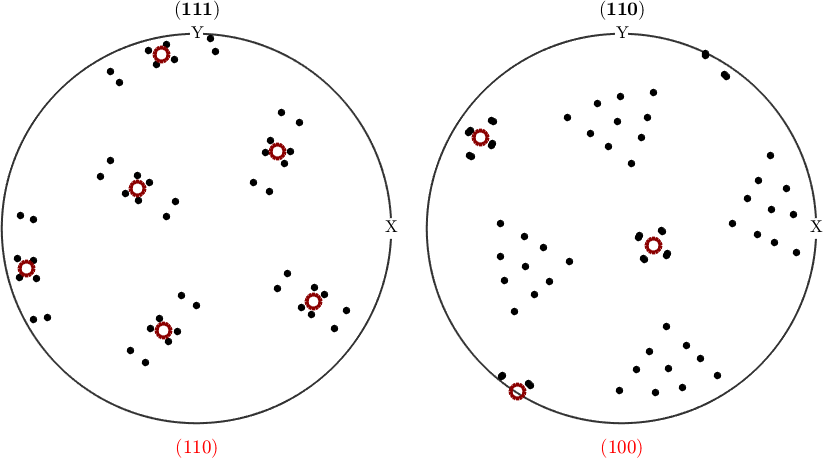

89.9532 72.3537 197.269These 12 Ferrite orientations are called variants of the orientation relationship. Lets visualize them in a pole figure plot

hC = Miller({1,1,1},{1,1,0},csC);

hP = Miller({1,1,0},{1,0,0},csP);

% plot the child variants

plotPDF(oriB,hC,'MarkerSize',5,'markerColor','black','figSize','medium');

% and on top the parent orientation

opt = {'MarkerFaceColor','none','MarkerEdgeColor','darkred','linewidth',3};

for k = 1:2

nextAxis(k)

hold on

plot(oriA * hP(k).symmetrise ,opt{:})

xlabel(char(hP(k),'latex'),'Color','red','Interpreter','latex')

hold off

end

drawNow(gcm)

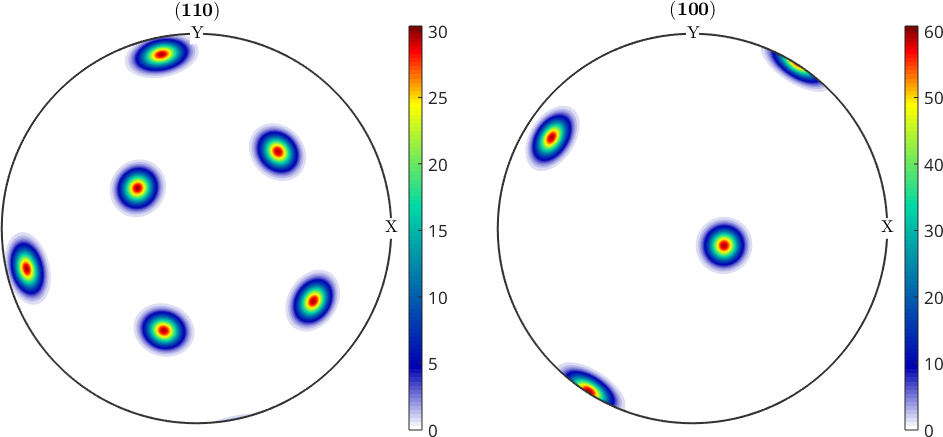

In case we have multiple parent orientations following some initial orientation distribution function odf

% define a model ODF

odfA = unimodalODF(oriA,'halfwidth',5*degree)

plotPDF(odfA,hP,'figSize','medium')

mtexColorbarodfA = SO3FunRBF (Austenite → y←↑x)

unimodal component

kernel: de la Vallee Poussin, halfwidth 5°

center: 1 orientations

Bunge Euler angles in degree

phi1 Phi phi2 weight

156.958 161.468 197.878 1

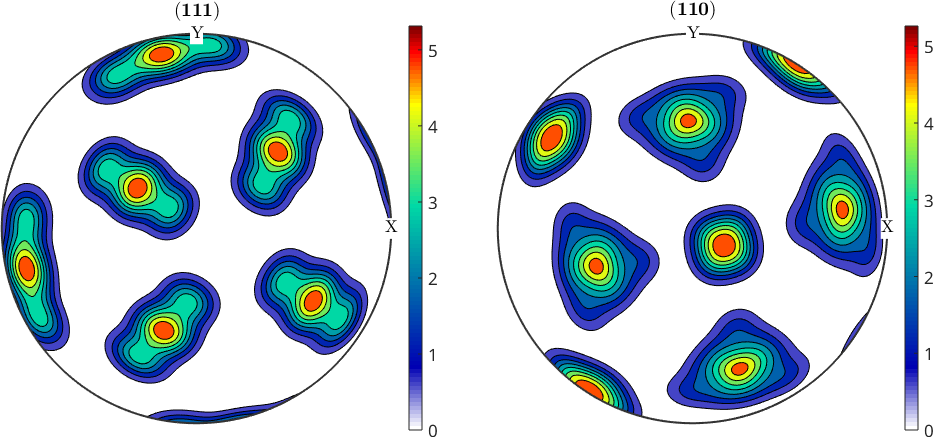

We can draw some random orientations according this model ODF and apply the same commands variants to compute all transformed orientations in one step

% number of discrete orientations

n = 10000;

oriASim = odfA.discreteSample(n)

% transform the orientations

oriBSim = variants(p2c,oriASim)

% show the result

plotPDF(oriBSim,hC,'contourf','figSize','medium');

mtexColorbaroriASim = orientation (Austenite → y←↑x)

size: 10000 x 1

oriBSim = orientation (Ferrite → y←↑x)

size: 10000 x 12

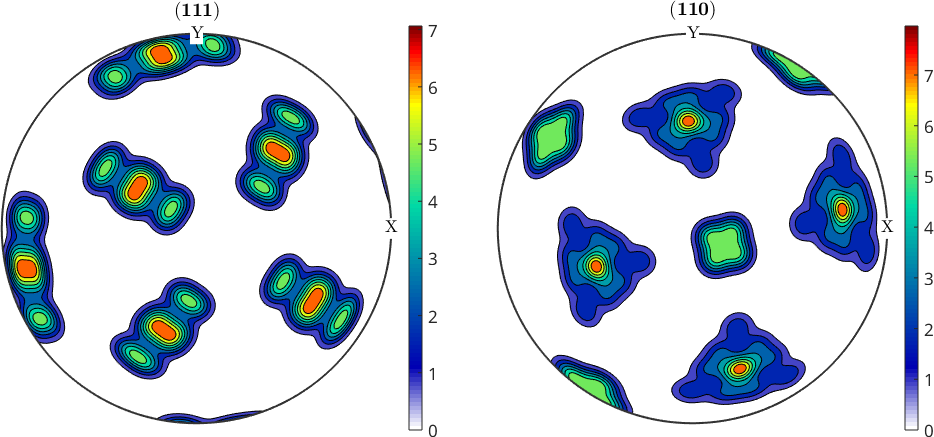

An alternative and better approach is to directly use odfA as an input to the function variants. In this case the output is the orientation distribution function of the transformed material

% compute the child ODF

odfB = variants(p2c,odfA)

% plot

plotPDF(odfB,hC,'contourf','figSize','medium');

mtexColorbarodfB = SO3FunHarmonic (Ferrite → y↑→x)

bandwidth: 48

weight: 1

We observe that the transformed ODF computed by the latter approach is sharper and shows more details when compared with the ODF computed from discrete orientations. We may quantify this difference by computing the texture index of both ODFs

% texture index of the transformed ODF computed from discrete orientations

odfBSim = calcDensity(oriBSim)

norm(odfBSim)^2odfBSim = SO3FunHarmonic (Ferrite → y←↑x)

bandwidth: 25

weight: 1

ans =

3.4854% texture index of the directly computed transformed ODF

norm(odfB)^2ans =

17.4509